Are Humans The Only Animals With Consciousness

Might we humans be the only species on this planet to be truly conscious? Might lobsters and lions, beetles and bats be unconscious automata, responding to their worlds with no hint of conscious experience? Aristotle thought and then, challenge that humans have rational souls only that other animals have only the instincts needed to survive. In medieval Christianity the "keen chain of being" placed humans on a level above soulless animals and beneath but God and the angels. And in the 17th century French philosopher René Descartes argued that other animals accept only reflex behaviors. Yet the more biology we larn, the more than obvious it is that nosotros share not only anatomy, physiology and genetics with other animals merely also systems of vision, hearing, memory and emotional expression. Could information technology really be that we alone accept an actress special something—this marvelous inner world of subjective experience?

The question is hard considering although your own consciousness may seem the most obvious affair in the world, it is perhaps the hardest to study. We do not even have a articulate definition across highly-seasoned to a famous question asked by philosopher Thomas Nagel back in 1974: What is it like to be a bat? Nagel chose bats considering they live such very dissimilar lives from our own. We may try to imagine what it is like to sleep upside down or to navigate the world using sonar, but does it feel similar annihilation at all? The crux here is this: If at that place is cypher information technology is like to exist a bat, we can say it is non conscious. If there is something (anything) it is similar for the bat, information technology is witting. Then is there?

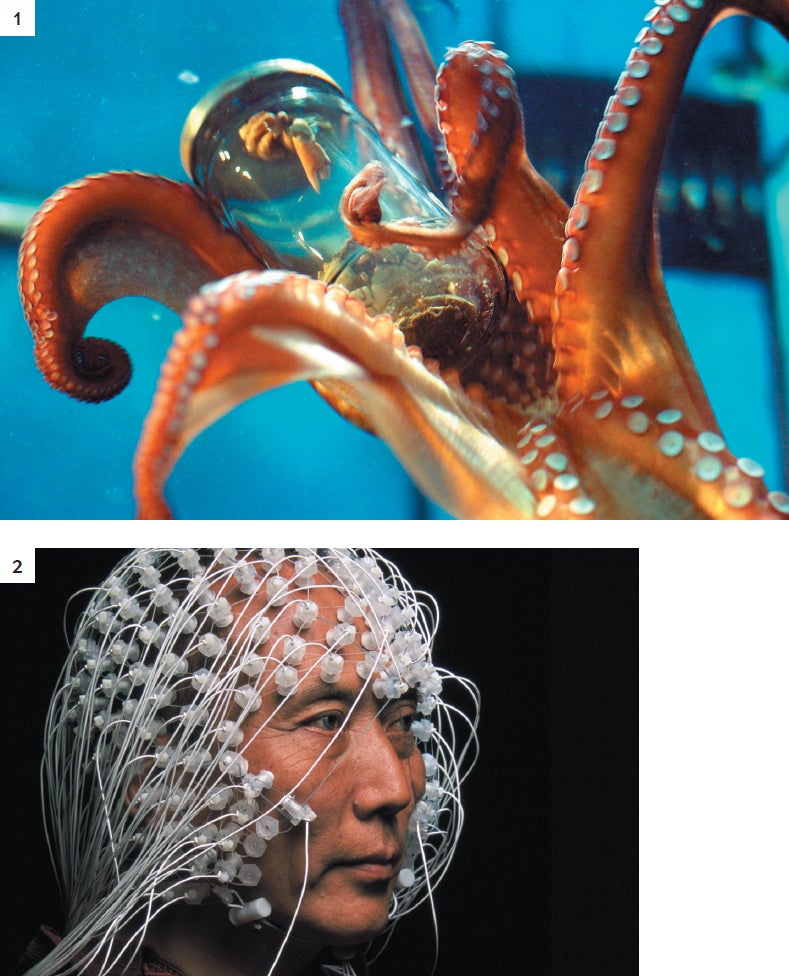

Nosotros share a lot with bats: we, too, have ears and tin imagine our artillery as wings. But endeavor to imagine being an octopus. Yous have viii curly, grippy, sensitive arms for getting around and catching prey but no skeleton, then you can squeeze yourself through tiny spaces. Simply a third of your neurons are in a central encephalon; the balance are in the nerve cords in each of your eight arms, one for each arm. Consider: Is it like something to exist a whole octopus, to be its cardinal encephalon or to be a single octopus arm? The science of consciousness provides no like shooting fish in a barrel manner of finding out.

Fifty-fifty worse is the "hard problem" of consciousness: How does subjective experience arise from objective brain activeness? How can concrete neurons, with all their chemical and electrical communications, create the feeling of pain, the glorious red of the sunset or the taste of fine blood? This is a problem of dualism: How tin can heed arise from affair? Indeed, does it?

The answer to this question divides consciousness researchers down the heart. On ane side is the "B Team," as philosopher Daniel C. Dennett described them in a heated debate. Members of this group agonize about the hard problem and believe in the possibility of the philosopher'southward "zombie," an imagined animal that is indistinguishable from you lot or me just has no consciousness. Assertive in zombies means that other animals might conceivably be seeing, hearing, eating and mating "all in the night" with no subjective feel at all. If that is so, consciousness must exist a special additional capacity that we might have evolved either with or without and, many would say, are lucky to have.

On the other side is the A Squad: scholars who turn down the possibility of zombies and think the hard problem is, to quote philosopher Patricia Churchland, a "hornswoggle problem" that obfuscates the outcome. Either consciousness just is the activity of bodies and brains, or information technology inevitably comes along with everything we so obviously share with other animals. In the A team's view, in that location is no point in asking when or why "consciousness itself" evolved or what its function is considering "consciousness itself" does not exist.

Suffering

Why does it thing? One reason is suffering. When I accidentally stamped on my true cat'due south tail and she screeched and shot out of the room, I was sure I had hurt her. Withal behavior can be misleading. We could hands place pressure sensors in the tail of a robotic cat to actuate a screech when stepped on—and nosotros would not think information technology suffered hurting. Many people become vegetarians because of the mode farm animals are treated, but are those poor cows and pigs pining for the cracking outdoors? Are bombardment hens suffering horribly in their tiny cages? Behavioral experiments show that although hens enjoy scratching about in litter and will choose a cage with litter if access is easy, they volition not carp to push aside a heavy drape to get to information technology. So do they non much intendance? Lobsters make a terrible screaming noise when boiled alive, but could this just exist air being forced out of their shells?

When lobsters or crabs are injured, are taken out of water or have a claw twisted off, they release stress hormones similar to cortisol and corticosterone. This response provides a physiological reason to believe they suffer. An even more telling sit-in is that when injured prawns limp and rub their wounds, this behavior can exist reduced by giving them the same painkillers as would reduce our own pain.

The same is true of fish. When experimenters injected the lips of rainbow trout with acetic acrid, the fish rocked from side to side and rubbed their lips on the sides of their tank and on gravel, but giving them morphine reduced these reactions. When zebra fish were given a choice between a tank with gravel and plants and a barren one, they chose the interesting tank. Merely if they were injected with acrid and the barren tank contained a painkiller, they swam to the barren tank instead. Fish pain may be simpler or in other ways different from ours, simply these experiments suggest they do feel pain.

.jpg)

Some people remain unconvinced. Australian biologist Brian Key argues that fish may respond as though they are in hurting, but this observation does not show they are consciously feeling annihilation. Baneful stimuli, he asserted in the open up-admission periodical Creature Sentience, "don't experience like anything to a fish." Human consciousness, he argues, relies on signal amplification and global integration, and fish lack the neural architecture that makes these connections possible. In result, Primal rejects all the behavioral and physiological evidence, relying on anatomy lonely to uphold the uniqueness of humans.

A World of Different Brains

If such studies cannot resolve the result, perhaps comparing brains might aid. Could humans exist uniquely conscious because of their big brains? British pharmacologist Susan Greenfield proposes that consciousness increases with brain size beyond the beast kingdom. But if she is right, and then African elephants and grizzly bears are more witting than you are, and Dandy Danes and Dalmatians are more conscious than Pekinese and Pomeranians, which makes no sense.

More relevant than size may be aspects of brain organization and function that scientists call up are indicators of consciousness. Almost all mammals and virtually other animals—including many fish and reptiles and some insects—alternate betwixt waking and sleeping or at least take strong cyclic rhythms of activity and responsiveness. Specific brain areas, such as the lower brain stem in mammals, command these states. In the sense of being awake, therefore, most animals are conscious. Still, this is not the aforementioned as asking whether they have witting content: whether at that place is something information technology is similar to exist an awake slug or a lively lizard.

Many scientists, including Francis Crick and, more recently, British neuroscientist Anil Seth, take argued that human consciousness involves widespread, relatively fast, depression-amplitude interactions between the thalamus, a sensory way station in the core of the encephalon, and the cortex, the gray matter at the encephalon's surface. These "thalamocortical loops," they claim, help to integrate information across the brain and thereby underlie consciousness. If this is correct, finding these features in other species should indicate consciousness. Seth concludes that because other mammals share these structures, they are therefore witting. Yet many other animals do not: lobsters and prawns have no cortex or thalamocortical loops, for example. Mayhap nosotros need more than specific theories of consciousness to find the critical features.

Among the most pop is global workspace theory (GWT), originally proposed by American neuroscientist Bernard Baars. The thought is that human brains are structured effectually a workspace, something like working memory. Any mental content that makes it into the workspace, or onto the brightly lit "stage" in the theater of the listen, is then broadcast to the rest of the unconscious brain. This global broadcast is what makes individuals conscious.

This theory implies that animals with no brain, such as starfish, sea urchins and jellyfish, could not be conscious at all. Nor could those with brains that lack the right global workspace architecture, including fish, octopuses and many other animals. Notwithstanding, every bit we accept already explored, a torso of behavioral testify implies that they are conscious.

Integrated information theory (IIT), originally proposed past neuroscientist Giulio Tononi, is a mathematically based theory that defines a quantity called Φ (pronounced "phi"), a measure of the extent to which data in a system is both differentiated into parts and unified into a whole. Various ways of measuring Φ atomic number 82 to the decision that large and complex brains similar ours have high Φ, deriving from amplification and integration of neural activity widely across the brain. Simpler systems accept lower Φ, with differences also arising from the specific arrangement found in dissimilar species. Dissimilar global workspace theory, IIT implies that consciousness might exist in simple forms in the lowliest creatures, besides as in appropriately organized machines with high Φ.

Both these theories are currently considered contenders for a true theory of consciousness and ought to assistance united states answer our question. But when it comes to fauna consciousness, their answers clearly conflict.

The Evolving Listen

Thus, our behavioral, physiological and anatomical studies all give mutually contradictory answers, as exercise the two virtually popular theories of consciousness. Might information technology help to explore how, why and when consciousness evolved?

Here again we run into that gulf betwixt the two groups of researchers. Those in the B Team assume that considering we are obviously witting, consciousness must take a function such as directing beliefs or saving usa from predators. Yet their guesses as to when consciousness arose range from billions of years ago correct upward to historical times.

For example, psychiatrist and neurologist Todd Feinberg and biologist Jon Mallatt proffer, without giving compelling evidence, an opaque theory of consciousness involving "nested and nonnested" neural architectures and specific types of mental images. These, they merits, are found in animals from 560 million to 520 meg years agone. Baars, the writer of global workspace theory, ties the emergence of consciousness to that of the mammalian encephalon around 200 meg years ago. British archaeologist Steven Mithen points to the cultural explosion that started threescore,000 years ago when, he contends, dissever skills came together in a previously divided brain. Psychologist Julian Jaynes agrees that a previously divided brain became unified only claims this happened much subsequently. Finding no evidence of words for consciousness in the Greek epic the Iliad, he concludes that the Greeks were non conscious of their own thoughts in the aforementioned way that we are, instead attributing their inner voices to the gods. Therefore, Jayne argues, until 3,000 years agone people had no subjective experiences.

Are whatever of these ideas correct? They are all mistaken, claim those in the A Squad, because consciousness has no independent function or origin: it is not that kind of thing. Team members include "eliminative materialists" such every bit Patricia and Paul Churchland, who maintain that consciousness but is the firing of neurons and that one day we will come to accept this just every bit we accept that light only is electromagnetic radiation. IIT besides denies a separate function for consciousness because any system with sufficiently loftier Φ must inevitably exist conscious. Neither of these theories makes human consciousness unique, but one final idea might.

This is the well-known, though much misunderstood, claim that consciousness is an illusion. This arroyo does not deny the beingness of subjective feel simply claims that neither consciousness nor the self are what they seem to be. Illusionist theories include psychologist Nicholas Humphrey'south idea of a "magical mystery show" being staged inside our heads. The brain concocts out of our ongoing experiences, he posits, a story that serves an evolutionary purpose in that information technology gives us a reason for living. Then there is neuroscientist Michael Graziano'due south attention schema theory, in which the brain builds a simplified model of how and to what it is paying attention. This idea, when linked to a model of cocky, allows the encephalon—or indeed any machine—to describe itself as having witting experiences.

By far the all-time-known illusionist hypothesis, however, is Dennett's "multiple drafts theory": brains are massively parallel systems with no central theater in which "I" sit viewing and controlling the world. Instead multiple drafts of perceptions and thoughts are continually processed, and none is either witting or unconscious until the organization is probed and elicits a response. Just then do we say the thought or activity was conscious; thus, consciousness is an attribution we make after the fact. He relates this to the theory of memes. (A meme is information copied from person to person, including words, stories, technologies, fashions and customs.) Considering humans are capable of widespread generalized simulated, nosotros lone can copy, vary and select amongst memes, giving ascension to linguistic communication and culture. "Human consciousness is itself a huge complex of memes," Dennett wrote in Consciousness Explained, and the self is a "'beneficial user illusion."

This illusory self, this complex of memes, is what I call the "selfplex." An illusion that nosotros are a powerful self that has consciousness and free will—which may non be so benign. Paradoxically, it may be our unique capacity for language, autobiographical memory and the imitation sense of being a continuing self that serves to increment our suffering. Whereas other species may feel pain, they cannot brand it worse past crying, "How long will this hurting concluding? Will it become worse? Why me? Why at present?" In this sense, our suffering may be unique. For illusionists such as myself, the answer to our question is unproblematic and obvious. We humans are unique because we alone are clever enough to be deluded into assertive that at that place is a witting "I."

This article was originally published with the title "The Hardest Problem" in Scientific American 319, 3, 48-53 (September 2018)

doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0918-48

More TO EXPLORE

The Character of Consciousness. David J. Chalmers. Oxford Academy Press, 2010.

Consciousness and the Brain: Deciphering How the Brain Codes Our Thoughts. Stanislas Dehaene. Viking, 2014.

From Leaner to Bach and Back: The Evolution of Minds. Daniel C. Dennett. Westward. Due west. Norton, 2017.

Consciousness: An Introduction. Third edition. Susan Blackmore and Emily T. Troscianko. Routledge, 2018.

FROM OUR ARCHIVES

What Is Consciousness? Christof Koch; June 2018.

Source: https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/are-humans-the-only-conscious-animal/

Posted by: grangerapoing.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Are Humans The Only Animals With Consciousness"

Post a Comment