What Can Be Planted In Garden After Tomatoes Were There The Previous Year

Crop Rotation for Growing Vegetables

The sight of large fields full of one type of crop ripening in the sun may now be a quintessential part of the countryside, but this mass-production method of cultivating a single species has long been known to cause problems.

Large groups of the same crop make an easy target for pests. For this reason, non-organic commercial growers feel compelled to spray the whole area with pesticides. Soil nutrients are depleted when the ground is occupied by a large number of the same type of plant. This problem is compounded if the ground is used for the same crop next season – often the soil becomes so impoverished that artificial fertilizers are needed. And soil subjected to the same mechanical processes year after year will inevitably become compacted.

While the gardener won't be growing as intensively as the farmer, these problems may also be encountered on a smaller scale. You may see a drop in plant health and productivity if crops are grown in the same spot for many years.

To avoid these pitfalls, adopt a crop rotation plan. The principle is straightforward enough – the same vegetables should not be planted in the same place year after year. As a system of organic gardening, crop rotation has many advantages:

- It lessens the need for pest control

- You reduce the spread of soil-borne disease

- It avoids nutrient depletion in the soil

Combined with other organic methods, rotation offers an excellent defense against all kinds of pests and disease.

How Crop Rotation Works

Simply divide your growing space into a number of distinct areas, identify the crops you want to grow and then keep plants of the same type together in one area. Every year the plants grown in each given area are changed, so that each group (with its own requirements, habits, pests and diseases) can have the advantage of new ground.

Most crop rotation schemes tend to run for at least three or four years, as this is the number of years it takes for most soil-borne pests and diseases to decline to harmless levels. If your beds are divided into four groups, this means that members of each plant family won't occupy the same spot more than once in a four-year period. Perennial vegetables such as soft fruit, rhubarb, asparagus and globe artichoke aren't replanted each year, so they may need their own dedicated bed.

The traditional advice is well intentioned, but also flawed. It recommends that you divide crops into four main groups as follows: Legumes (bush beans, peas, pole beans, broad beans); root vegetables (radish, carrot, potato, onion, garlic, beet, rutabaga, sweet potato, shallots); leafy greens (spinach, chard, kale, cabbage, cauliflower, broccoli, spinach); and fruit-bearing(tomato, sweetcorn, cucumber, squash, pumpkin, zucchini, eggplant).

Limitations of the Traditional Method of Crop Rotation

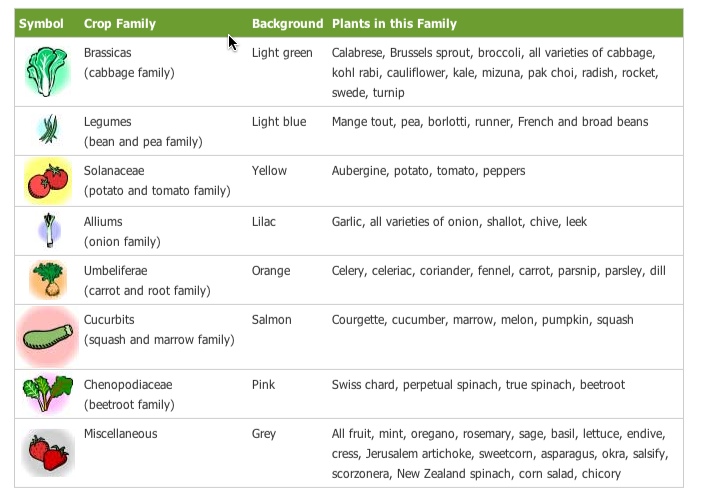

While it is certainly beneficial to move crops around, this practice on its own is somewhat hit and miss. What's more, such simplified groups don't tell the whole story, as the growth habit (i.e. root, fruit, leaf etc) does not bear on the classification of the plant. For instance, although they appear radically different, potato and tomato are in fact members of the same family. According to the traditional scheme one could follow the other, but since they are so closely related, they will attract the same pests and use up the same nutrients from the soil. To avoid this type of confusion, our Garden Planner tool uses a more sophisticated classification system which is convenient color-coded for ease of use:

These categories offer greater flexibility and allow a wider permutation of crops grown over the seasons. . In addition, our Garden Planner allows you to look back over five years of your plot's history, warning you when you try to replant the same crop too soon and making it easier to design a longer rotation plan.

Some vegetables are not prone to soil-borne disease, which means that they don't need to be part of your rotation plan. You can therefore sow plants from the Miscellaneous group (grey) wherever you have free space. Members of the Chenopodiaceae (pink) family, such as beets and spinach are also relatively unproblematic, and can follow most other crops.

Planning the Order of Crop Rotation

Brassicas follow legumes: Sow crops such as cabbage, cauliflower and kale on soil previously used for beans and peas. The latter fix nitrogen in the soil, whilst the former benefit from the nutrient-rich conditions thus created. Potatoes also love nitrogen-rich soil, but should not be planted alongside brassicas as they like different pH levels.

Very rich soil and roots don't mix: Avoid planting root vegetables on areas which have been heavily fertilized, as this will cause lush foliage at the expense of the edible parts of the plant. Sow parsnip on an area which has housed demanding crops (such as brassicas) the previous season, since they will have broken down the rich compounds.

Example of a Four-bed Rotation

- Area 1: Enrich area with compost and plant potatoes and tomatoes (Solanaceae). When crop has finished sow onions or leeks (Allium) for an overwinter crop.

- Area 2: Sow parsnips, carrot, parsley (Umbelliferae). Fill gaps with lettuce and follow with a soil-enriching green manure during winter.

- Area 3: Grow cabbage, kale, rocket (Brassicas) during the summer and follow with winter varieties of cabbage and Brussels sprouts.

- Area 4: If this is your second or subsequent year, harvest the onions or leeks previously growing here over winter. Then sow peas and beans (legumes). When harvest has finished, lime the soil for brassicas which will move from area three to occupy the space next.

< All Guides

What Can Be Planted In Garden After Tomatoes Were There The Previous Year

Source: https://www.growveg.com/guides/crop-rotation-for-growing-vegetables/

Posted by: grangerapoing.blogspot.com

0 Response to "What Can Be Planted In Garden After Tomatoes Were There The Previous Year"

Post a Comment